jean-michel basquiat (1960 - 1988)

YAYOI Kusama (born 1929)

Ed ruscha (born 1937)

|

As with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, his East Coast counterparts, Ed Ruscha’s artistic training was rooted in commercial art. His interest in words and typography ultimately provided the primary subject of his paintings, prints and photographs. The very first of Ruscha's word paintings were created as oil paintings on paper in Paris in 1961. Since 1964, Ruscha has been experimenting regularly with painting and drawing words and phrases, often oddly comic and satirical sayings alluding to popular culture and life in LA. When asked where he got his inspiration for his paintings, Ruscha responded, “Well, they just occur to me; sometimes people say them and I write down and then I paint them. Sometimes I use a dictionary.”

|

Q & A

What is the meaning “ace,” a word used early and often by the artist?

“Ace” appears as a single word in six works by Ed Ruscha created early in his career (1961 – 1963), and is included with the words “radio,” “honk,” and “boss” in two additional paintings on paper also from 1961. The word reappears in the artist’s work in the early 2000s in two large paintings. See all "ace" paintings here.

Ruscha has spoken often about his attraction to words that have strong visual impact, but he remains evasive when pressed to explain the specific meanings behind his word choices. “Ace” offers many complex associations. As a noun: a playing card that is both the “highest” and “lowest” in games; a person who excels, an expert. As an adjective: excellent, first-rate, superlative, or skillful. In common slang: a dollar bill, a close friend, an amphetamine pill, or a grade of A on a test.

“Ace” appears within other words also popular with the artist (face, space, place, surface). Its powerful ending “s” sound is echoed in other Ruscha favorites (boss, yes, business). In 1985, interviewer Jana Sterbak asked Ruscha: “How do you come up with phrases for your paintings?”

Some are found readymade, some are dreams, some come from newspapers. They are finished by blind faith. No matter if I’ve seen it on television or read it in the newspaper, my mind seems to wrap itself around that thing until it’s done. It’s strange, I don’t know what motivates me, but each of the works is premeditated. I don’t stand in front of a blank canvas waiting for inspiration. At one time I loved the word “ace.” It meant something to me that was powerful. I made a few paintings of the word. I always like monosyllabic words like “smash” and “honk.” Single words kept my interest for a while and then, later, there was only one thing to do— heap more words in. Until finally, I found myself doing a painting which says, Study of Friction and Wear on Mating Surfaces [1983]. I keep notebooks. The initial ideas are written out. I don’t draw them, I stage them onto the canvas. I had an idea for this drawing called “Nerves.” I saw it as a capital “N” and then a lot of space and then “erves” and, in between, a line. I see this thing and being a good little art soldier, I go and do it. I just put the questions out. I don’t sit there thinking “Why am I doing this?” There is no answer. [Originally published in Real Life Magazine, No. 14, Summer 1985, pp. 26 – 29. Reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (October Books, MIT Press, 2002), page 253.]

Ruscha has spoken often about his attraction to words that have strong visual impact, but he remains evasive when pressed to explain the specific meanings behind his word choices. “Ace” offers many complex associations. As a noun: a playing card that is both the “highest” and “lowest” in games; a person who excels, an expert. As an adjective: excellent, first-rate, superlative, or skillful. In common slang: a dollar bill, a close friend, an amphetamine pill, or a grade of A on a test.

“Ace” appears within other words also popular with the artist (face, space, place, surface). Its powerful ending “s” sound is echoed in other Ruscha favorites (boss, yes, business). In 1985, interviewer Jana Sterbak asked Ruscha: “How do you come up with phrases for your paintings?”

Some are found readymade, some are dreams, some come from newspapers. They are finished by blind faith. No matter if I’ve seen it on television or read it in the newspaper, my mind seems to wrap itself around that thing until it’s done. It’s strange, I don’t know what motivates me, but each of the works is premeditated. I don’t stand in front of a blank canvas waiting for inspiration. At one time I loved the word “ace.” It meant something to me that was powerful. I made a few paintings of the word. I always like monosyllabic words like “smash” and “honk.” Single words kept my interest for a while and then, later, there was only one thing to do— heap more words in. Until finally, I found myself doing a painting which says, Study of Friction and Wear on Mating Surfaces [1983]. I keep notebooks. The initial ideas are written out. I don’t draw them, I stage them onto the canvas. I had an idea for this drawing called “Nerves.” I saw it as a capital “N” and then a lot of space and then “erves” and, in between, a line. I see this thing and being a good little art soldier, I go and do it. I just put the questions out. I don’t sit there thinking “Why am I doing this?” There is no answer. [Originally published in Real Life Magazine, No. 14, Summer 1985, pp. 26 – 29. Reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (October Books, MIT Press, 2002), page 253.]

The painting Ace (1961) was inscribed and gifted to Robert Rauschenberg (1925 – 2008),

an artist Ed Ruscha considered to be an early and powerful inspiration.

What is known about their connection and how does it impact the market value of this work of art?

an artist Ed Ruscha considered to be an early and powerful inspiration.

What is known about their connection and how does it impact the market value of this work of art?

In 1957, Ruscha saw a reproduction of Jasper Johns' Target with Four Faces (1955) and a Robert Rauschenberg's “combine” painting in Print Magazine. He described how he "knew from then on that I was going to be a fine artist.” When asked more than 20 years later what it was about the work of Johns and Rauschenberg that so excited him, Ruscha answered:

It was a voice from nowhere, it was a voice that I guess I needed; I needed to hear this and see this work. And it came to me, oddly enough, through the medium of reproduction, and so it was a printed page I was responding to . . . the kind of odd vocabulary they used inspired me – it was like music that you’ve never heard before, so mysterious and sweet, and I just dreamed about it at night. It was so powerful that I was wondering, “What are these guys, who are these people, what are they doing?” I began looking for more of their work. Each successive thing I saw by these men was a great work of art to me. It meant more to me than anything else. These new voices I was hearing transplanted the temporary excitement I had from Abstract Expressionism . . .” [Interview with Paul Karlstrom, “Interview with Ruscha in His Hollywood Studio,” 1980-1981, reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (October Books, MIT Press, 2002), pages 116 – 117. ]

Because of the inscription, it is assumed that Ruscha gifted (or traded) the painting Ace (1961), one of his most confident early works, to Rauschenberg, but the exact date of the gift is undocumented. Although Ruscha was deeply affected by the older artist's work throughout the late 50s and 60s, it seems likely the inscription and gift occurred sometime in the 1970s, after Ruscha began exhibiting in New York at the Leo Castelli Gallery. After 1982, Rauschenberg is listed as the owner of the painting in various exhibition checklists (see especially the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's exhibition, The Works of Edward Ruscha [March 25 - May 23, 1982]).

Although Rauschenberg lived primarily in New York, NY, and Captiva Island, FL, both artists worked periodically with Gemini G.E.L., the art print company based in Los Angeles, Ed Ruscha's home for many years. Rauschenberg created editions of his works in collaboration with Gemini from 1972 until 2000; Ruscha’s first print was executed in 1976 and his latest was completed in 2016.

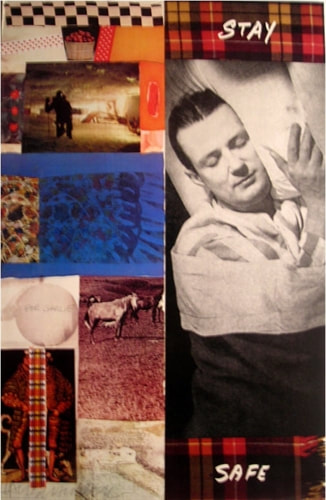

In 1978 at Rauschenberg’s invitation, Ruscha collaborated on a poster design, printed in an edition of 200, to raise funds for Change, Inc., Rauschenberg’s non-profit organization created to support struggling artists.

This color offset lithograph print is described as the result of “a rare collaboration between Ed Ruscha and Robert Rauschenberg," and there is scant evidence of any deep connection or personal friendship between the two. Rauschenberg is not listed as a correspondent in the ER papers (Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin).

There are three citations mentioning Ruscha in the Robert Rauschenberg Archives in New York. An email query to the archives requesting more information is pending a response. These citations include:

Lauren Oliver and Sam Orlofsky at the Gagosian Gallery have also been contacted by email, and a response is pending.

It was a voice from nowhere, it was a voice that I guess I needed; I needed to hear this and see this work. And it came to me, oddly enough, through the medium of reproduction, and so it was a printed page I was responding to . . . the kind of odd vocabulary they used inspired me – it was like music that you’ve never heard before, so mysterious and sweet, and I just dreamed about it at night. It was so powerful that I was wondering, “What are these guys, who are these people, what are they doing?” I began looking for more of their work. Each successive thing I saw by these men was a great work of art to me. It meant more to me than anything else. These new voices I was hearing transplanted the temporary excitement I had from Abstract Expressionism . . .” [Interview with Paul Karlstrom, “Interview with Ruscha in His Hollywood Studio,” 1980-1981, reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (October Books, MIT Press, 2002), pages 116 – 117. ]

Because of the inscription, it is assumed that Ruscha gifted (or traded) the painting Ace (1961), one of his most confident early works, to Rauschenberg, but the exact date of the gift is undocumented. Although Ruscha was deeply affected by the older artist's work throughout the late 50s and 60s, it seems likely the inscription and gift occurred sometime in the 1970s, after Ruscha began exhibiting in New York at the Leo Castelli Gallery. After 1982, Rauschenberg is listed as the owner of the painting in various exhibition checklists (see especially the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's exhibition, The Works of Edward Ruscha [March 25 - May 23, 1982]).

Although Rauschenberg lived primarily in New York, NY, and Captiva Island, FL, both artists worked periodically with Gemini G.E.L., the art print company based in Los Angeles, Ed Ruscha's home for many years. Rauschenberg created editions of his works in collaboration with Gemini from 1972 until 2000; Ruscha’s first print was executed in 1976 and his latest was completed in 2016.

In 1978 at Rauschenberg’s invitation, Ruscha collaborated on a poster design, printed in an edition of 200, to raise funds for Change, Inc., Rauschenberg’s non-profit organization created to support struggling artists.

This color offset lithograph print is described as the result of “a rare collaboration between Ed Ruscha and Robert Rauschenberg," and there is scant evidence of any deep connection or personal friendship between the two. Rauschenberg is not listed as a correspondent in the ER papers (Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin).

There are three citations mentioning Ruscha in the Robert Rauschenberg Archives in New York. An email query to the archives requesting more information is pending a response. These citations include:

- Correspondence (Personal), COR-P11, from 1978: presumed to be related to the “Stay Safe” poster project for Change, Inc.

- Photographs: Box 27 and 51: Two photos of the artist with Ed Ruscha (dated to the early 1990s) are logged.

- Interviews with Friends and Associates, Box 2, Folder 17 (contents unknown).

Lauren Oliver and Sam Orlofsky at the Gagosian Gallery have also been contacted by email, and a response is pending.

video links

Los Angeles MCA | Ed Ruscha: Buildings with Words | July 2016

Tate London | Ed Ruscha - The Tension of Words (TateShots) | May 23, 2013

research media

Words with Ruscha | Howardina Pindell, 1973

|

Ms. Pindella is an American abstract artist. Her work explores texture, color, structures, and the process of making art. The MCA Chicago featured her work in a solo exhibition in 2018.

|

Interview with Ruscha published in The Print Collector's Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 6 (January - February 1973), pp. 125-128.

|

Oral History Transcript | Paul Karlstrom Interviewer, 1981

|

Mr. Karlstrom was the West Coast Regional Director of the Archives of American Art from 1973 - 2003. Based in San Franciso, and Los Angeles, he is a free-lance art writer and interviewer.

|

Conversation with the artist for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

129 pages, see especially page 28, 29, 30, 32, and 69. |

Framing Words: Visual Language in Contemporary Art

Rochelle E. Steiner, University of Rochester PhD Thesis, 1996

Rochelle E. Steiner, University of Rochester PhD Thesis, 1996

|

Ms. Steiner joined the Vancouver Art Gallery as Associate Director and Chief Curator in April 2018. She also works as a professor of critical studies at the Roski School of Art and Design, the University of Southern California. She is a chief curator of the Serpentine Galleries in London.

|

A dissertation discussion of the "word" works of Edward Ruscha, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Louise

Lawler, and Lawrence Weiner. 198 pages, see especially Chapter 2: Toward a Visual Semiotics, beginning on sheet 43. Discussion of "ace" and other words, beginning on sheet 56 and continuing through sheet 87. |

Ed Ruscha's LA | New Yorker Magazine Profile, Calvin Tomkins, July 2013

|

Mr. Tomkins has been a staff writer for The New Yorker since 1960. He's profiled many artists, including Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns.

|

Back to the Drawing Board: Ed Ruscha 1956 - 68

Jennifer E. Quick, Harvard University PhD Thesis, 2015

Jennifer E. Quick, Harvard University PhD Thesis, 2015

|

Ms. Quick is the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Associate Research Curator in Photography at the Harvard Art Museums. She specializes in the history of photography and modern and contemporary art. She continues to write and publish on Ruscha's work.

|

in process

Christopher wool (born 1955)